Classic style Chinese paper windows. Note the wooden decorative work is support for the paper.

In many film and television dramas, assassins clad in black night clothes are depicted lurking in courtyards, piercing paper-covered windows to spy indoors. However, the reality of window coverings in ancient China evolved significantly before paper became standard.

Before the invention of durable, usable paper, window coverings were made from silk, linen, or sandpaper. In noble households, silk cloth was often used, adding a level of luxury and privacy, while common households relied on linen or sandpaper soaked in tung oil. This treatment made sandpaper both waterproof and translucent, allowing diffused light into rooms, much like today’s frosted glass.

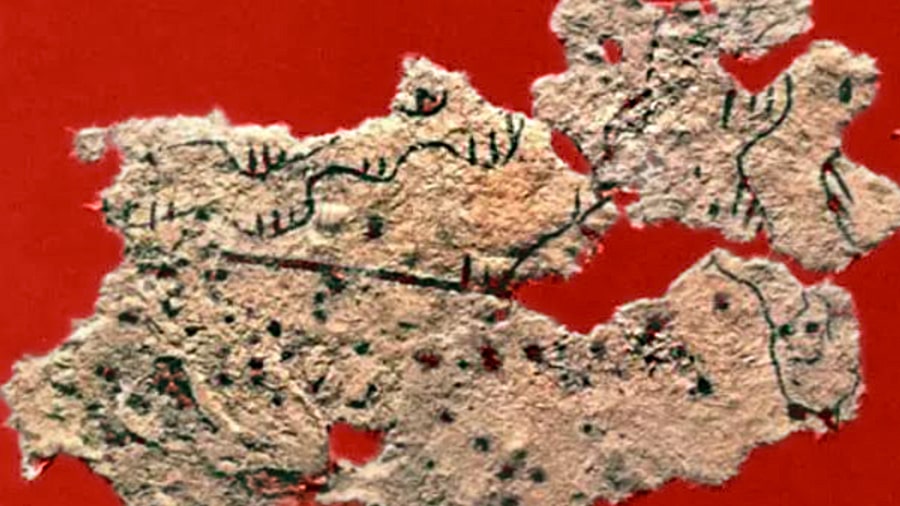

While early forms of paper existed in the Western Han 西漢 dynasty (206 BC–9 AD), they were coarse and initially unsuitable for daily use. Cai Lun’s 蔡倫 invention (105 AD) improved paper quality, but until then, paper had limited applications, mainly in military mapping, as shown by a 176–141 BC piece of hemp paper from the Fangmatan 放馬灘遺址 archeological site in Gansu 甘肅省. This early paper, painted with maps, was impractical for windows.

A fragment of a hemp paper map c.176 – 141 BCE. Fangmatan archeological site 放馬灘遺址, Gansu 甘肅省, China 中國

Only in later dynasties, when paper production became more refined and affordable, did window paper become common in homes. Nobles used patterned paper for elegance, while ordinary people favoured plain white paper for practicality. Paper windows enhanced room brightness but were fragile, requiring skilled craftsmen to replace torn paper after storms or high winds – similar to changing window screens today.

The phrase breaking the window paper 捅破窗紙 emerged as a metaphor, symbolising the act of revealing hidden truths, much like an assassin observing through a pierced window. This metaphor is yet another link to the culture of stealth arts of Chinese history.