The Five Punishments 五刑 were a cornerstone of the ancient Chinese penal system, representing the structured and often harsh methods by which the Chinese state dealt with crime and disorder. These punishments evolved over time, reflecting shifts in legal, philosophical, and political attitudes. While rooted in justice, they were also used to maintain authority and social order. This essay explores the origins, functions, and transformations of the Five Punishments 五刑 throughout China’s long history.

Origins of the Five Punishments 五刑

The Five Punishments 五刑 can be traced back to the Shang dynasty 商朝 (1600–1046 BCE) and are documented in early legal texts. Initially, they were deeply physical in nature, reflecting a society where law enforcement relied heavily on corporal punishment to assert authority and control. They represented a system of retributive justice, where physical penalties matched the severity of the crime.

During the Zhou dynasty 周朝 (1046–256 BCE), the legal framework became more formalised. The concept of the Five Punishments 五刑 was recorded in texts like the Book of Documents 書經, or Shū Jīng 書經, and their use was institutionalised. These punishments were reserved for serious transgressions and were designed to be exemplary, deterring crime by showcasing the severe consequences of offending against the state or social norms.

The Five Punishments 五刑 in the Qin 秦朝 and Han 漢朝 Dynasties

The Five Punishments 五刑 saw their codification under the Qin dynasty 秦朝 (221–206 BCE), which laid the foundation for much of China’s legal tradition. During this period, law was characterised by the principles of Legalism, which emphasised strict, uncompromising enforcement. Harsh punishments were believed to create order in society. The punishments were physically brutal and often permanent, designed to incapacitate the offender and serve as a lasting symbol of the state’s authority.

The Han dynasty 漢朝 (206 BCE–220 CE) inherited and modified these penal traditions. Confucian values began to merge with Legalist principles, creating a more balanced view of punishment, but the physical brutality of the Five Punishments 五刑 remained a central feature of the legal system.

The Original Five Punishments 五刑

During the early dynastic periods, the Five Punishments 五刑 were:

-

Tattooing 墨 mò: The criminal’s face or forehead would be marked with ink to permanently identify them as a lawbreaker. The punishment was meted out with a chisel and mallet, then the ink was poured into the wound. This served as a visible (and painful) reminder of their transgression, socially stigmatising them for life.

-

Cutting off the nose 劓 yì: A brutal punishment designed to disfigure the criminal permanently. The loss of the nose symbolised the individual’s moral and physical deformity. The body damage was considered deeply shameful, even if the accused managed to endure the pain and shock of the event. This punishment likely gave rise to the Chinese expression ‘to lose face’ or to experience profound humiliation.

-

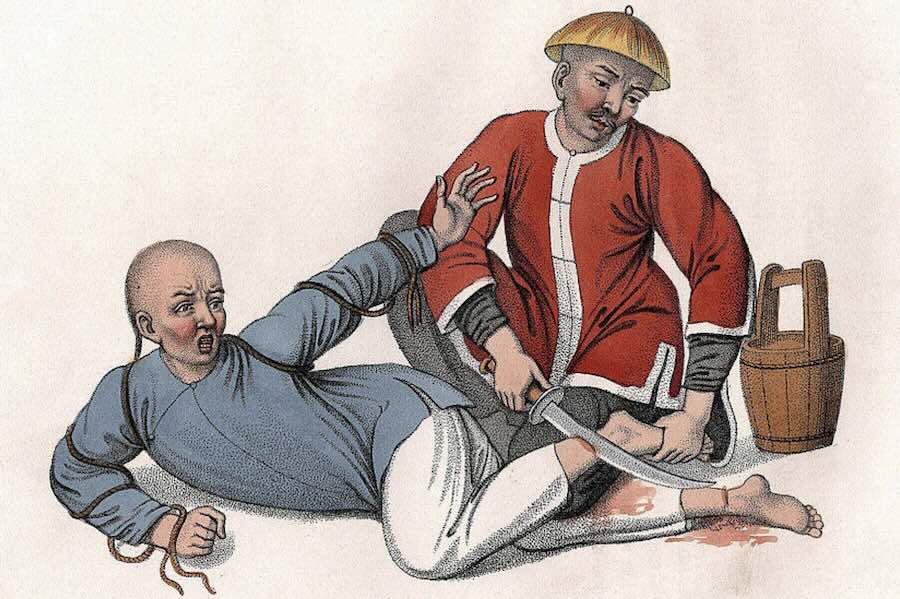

Amputation of the feet 刖 yuè: This penalty not only incapacitated the offender but also stripped them of the ability to function fully within society, serving as a lasting reminder of their crime.

-

Castration 宮 gōng: Typically reserved for severe crimes, castration served both as punishment and as a method to prevent the criminal from producing offspring, thus impacting their lineage. Similar procedures were sometimes performed on women, referred to as ‘taking out the ovaries’ 幽閉, all without anaesthetic.

-

Death 大辟 dà pì: This was the ultimate punishment, often carried out through beheading or other means, depending on the severity of the crime. The ultimate punishment involved methods such as cutting the body into four pieces 分為戮, boiling [alive] 烹, tearing off the offender’s head and limbs using chariots 車裂, beheading 梟首, execution followed by abandonment of the body in the public market 棄市, strangulation 絞, and slow slicing 凌遲.

These early punishments were heavily physical, with an emphasis on marking or maiming the body as a means of deterrence. However, they were also symbolic, reflecting the Confucian notion that moral and physical health were intertwined.

The Nine Steps of Punishment: Extending Retribution to the Family

While the Five Punishments 五刑 were primarily individual and physical in nature, ancient China also employed a more severe form of punishment known as the Nine Steps of Punishment 九族刑. This system reflected the belief that serious crimes, particularly those involving treason or betrayal of the state, endangered the entire social order and could not be dealt with through individual punishment alone. As such, the offender’s entire family—both immediate and extended—would be implicated and punished, often with death or lifelong exile.

The Nine Steps of Punishment 九族刑 aimed to eliminate potential threats to the ruling regime by wiping out the criminal’s bloodline, including their ancestors, descendants, and collateral relatives. This was seen not only as a means of deterring rebellion and treason but also as a way of ensuring that no one from the offender’s lineage would seek revenge or challenge the state in the future. It was a punishment designed to serve as an extreme warning to anyone considering crimes against the Emperor or the state.

The Case of Jing Ke 荊軻: Punishing Treason Through Collective Retribution

One of the most notorious examples of this principle was the case of Jing Ke 荊軻, a would-be assassin who attempted to kill Qin Shi Huang 秦始皇, the First Emperor of China. Though Jing Ke 荊軻 failed in his mission, his crime was deemed so severe that the Emperor ordered the extermination of not just Jing Ke 荊軻 himself, but his entire family, in accordance with the Nine Steps of Punishment 九族刑. This act of collective punishment served two purposes: to eliminate any future threats from his bloodline and to reinforce the Emperor’s absolute authority.

The philosophy behind this severe punishment system was grounded in the belief that a single person’s treachery could corrupt an entire family, and only through the complete eradication of the criminal’s clan could the threat be fully neutralised. The Nine Steps of Punishment 九族刑 also acted as a profound deterrent, reminding the populace that crimes against the state would result not just in individual suffering but in the annihilation of one’s familial legacy.

The Collective Nature of Punishment in Ancient China

The concept of collective responsibility in ancient Chinese law reflects the Confucian emphasis on familial ties and loyalty to authority. The Nine Steps of Punishment 九族刑 was designed to reinforce these values by ensuring that treasonous acts were not seen merely as individual transgressions but as offenses that undermined the entire family unit and, by extension, society itself. This harsh system encouraged people to police their own family members and discouraged potential rebels from risking not only their own lives but also the lives of their loved ones.

The legal and moral underpinning of the Nine Steps of Punishment 九族刑 reveals the extent to which maintaining order, stability, and loyalty to the Emperor were considered paramount in ancient China. This principle of collective punishment, though extreme, was part of the state’s broader strategy for maintaining control over a large and diverse population. It also illustrates how punishment in ancient China extended beyond physical retribution to target the social and familial fabric of the nation.

Transformation During the Sui 隋朝 and Tang 唐朝 Dynasties

With the advent of the Sui dynasty 隋朝 (581–618 CE) and Tang dynasty 唐朝 (618–907 CE), the legal system underwent significant reforms. The Tang Code 唐律 Táng Lǜ, which emerged during this period, sought to introduce a more structured and ethical approach to justice, influenced by Confucian ideals. The Five Punishments 五刑 were revised to reflect this shift towards greater leniency and proportionality in punishment.

Under the Tang 唐朝 legal system, the emphasis on permanent physical mutilation began to wane, replaced by punishments that were still harsh but less disfiguring. These revised punishments included:

-

Beating with light bamboo 笞刑 chī xíng: A milder form of corporal punishment, involving a certain number of strokes administered with a bamboo cane.

-

Beating with heavy bamboo 杖刑 zhàng xíng: A more severe form of caning, used for more serious offenses.

-

Penal servitude 徒刑 tú xíng: Offenders were forced to perform hard labour for a specified period.

-

Exile 流刑 liú xíng: Criminals were banished to remote regions, often with harsh climates and poor conditions, far from their families and communities.

-

Death 死刑 sǐ xíng: Capital punishment remained the most severe penalty, but it was now reserved for the gravest offenses, and Confucian ideals began to encourage mercy in certain circumstances.

These changes reflected a more humane approach to justice, with the penal system becoming less focused on brutal retribution and more on rehabilitation and social reintegration where possible.

Confucian Influence and the Song Dynasty 宋朝 Reforms

By the Song dynasty 宋朝 (960–1279 CE), Confucian ideals of humaneness and justice had fully permeated the legal system. The Five Punishments 五刑 continued to evolve, with increasing emphasis on moderation, proportionality, and the restoration of social harmony rather than simply punishing offenders. Exile, penal servitude, and caning became more common, while mutilation was largely phased out.

Confucian scholars argued that punishment should serve not only to deter crime but also to rehabilitate the criminal and promote the moral betterment of society as a whole. The legal system now aimed at reintegrating offenders into society rather than permanently marking them as outcasts.

The Decline of Physical Punishments in the Ming 明朝 and Qing 清朝 Dynasties

By the time of the Ming dynasty 明朝 (1368–1644 CE) and Qing dynasty 清朝 (1644–1912 CE), the penal system had undergone significant transformations. The Five Punishments 五刑, in their original form, were rarely used. Milder forms of corporal punishment, fines, and exile became the norm. The harshest physical punishments were reserved for only the most serious crimes, such as rebellion or high treason.

The Qing dynasty 清朝 introduced further reforms to legal procedures, aiming for greater fairness and justice in trials. Capital punishment was carefully scrutinised, with cases often reviewed by multiple levels of government to ensure that the death penalty was not abused. These measures reflected an increasing awareness of the need for justice that balanced authority with individual rights, showcasing a gradual shift from the extreme retribution characteristic of earlier dynasties to a more nuanced approach to law.

References

-

Baker, H. (1996). Punishment in China: The Role of the Judiciary. Routledge.

-

Chen, P. (1993). Chinese Law: A Bibliography. New York: The University Press of America.

-

Deng, Y. (2003). The Confucian Approach to Justice: Ancient and Modern Perspectives. Journal of Chinese Philosophy, 30(1), 43-56.

-

Feng, X. (2011). Legal Culture in the People’s Republic of China. In Asian Legal Cultures (pp. 102-123). Routledge.

-

Huang, W. (2008). The Tang Code: A Legal Code in Transition. In The Cambridge History of Ancient China (pp. 775-815). Cambridge University Press.

-

Jiang, H. (2012). The Role of Law in Chinese Society: Historical Perspectives and Contemporary Issues. China Review International, 19(2), 173-193.

-

Klein, H. (2008). The Criminal Justice System in China: Reforming the System of Criminal Punishment. In The Handbook of Chinese Law (pp. 320-338). Wiley.

-

Li, C. (2005). An Overview of the Historical Development of Chinese Criminal Law. Journal of East Asian Law, 1(1), 15-30.

-

Pang, H. (2006). Justice in Ancient China: Confucianism and the Development of Legal Thought. China Journal of Law, 24(3), 45-65.

-

Zhang, Q. (2000). The Philosophy of Law in Ancient China: From the Zhou to the Han Dynasties. In Chinese Philosophy: A Philosophical History (pp. 120-135). Blackwell Publishing.

Online Resources

-

Deng, Y. (2009). Historical and Cultural Contexts of Chinese Legal Traditions. Available at: Asia Pacific Law Review

-

Wang, J. (2014). Legalism and Confucianism in Chinese History. Available at: Academia.edu