The earliest recorded instance of stealth in Chinese strategic warfare occurred in 594 BCE when the Song 宋 capital, under siege for five gruelling months, found itself in a state of desperation. In response, the Song 宋 leadership sent Hua Yuan 華元 on a perilous stealth mission to force an agreement from Zi Fan 子反, the commander of the besieging Chu 楚 forces.

The people of Song 宋, gripped with fear, entrusted Hua Yuan 華元 to penetrate the Chu 楚 camp by night.

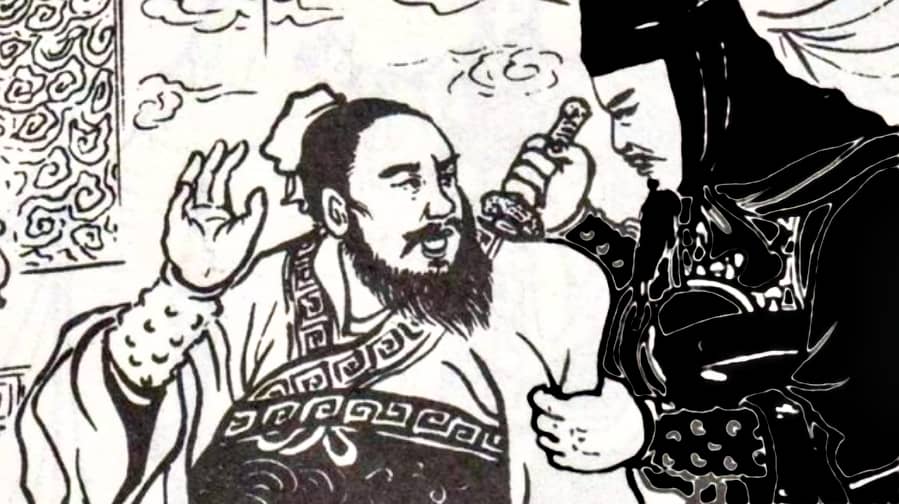

He silently entered Zi Fan’s 子反 quarters and sat upon the general’s bed, awakening him. Hua Yuan 華元 declared, ‘My lord has commanded me to inform you of our extreme plight. In our city, the people have resorted to exchanging their children to eat, breaking bones to use as fuel for their fires. Despite this, we will never submit to an agreement made under duress, even if it leads to our state’s destruction. However, if you withdraw your forces by thirty li [distance measurement], we will obey your commands.’

Shocked by Hua Yuan’s 華元 daring penetration into his inner sanctum, Zi Fan 子反, fearing for his safety, swore an oath and reported the situation to the King of Chu 楚. The Chu 楚 army subsequently withdrew by thirty li. [as per Zi Fan’s 子反 promise]. Hua Yuan 華元 was taken as a hostage to ensure peace, and a treaty was forged: Song 宋 would not deceive Chu 楚, nor would Chu 楚 harm Song 宋.

宋人懼,使華元夜入楚師,登子反之床,起之曰,寡君使元以病告,曰,敝邑易子而食,析骸以爨。雖然,城下之盟,有以國斃,不能從也,去我三十里,唯命是聽,子反懼,與之盟,而告王。退三十里,宋及楚平,華元為質。盟曰:我無爾詐,爾無我虞。

This account of Hua Yuan 華元 is a striking example of stealth tactics of the time, illustrating his ability to pass through Chu 楚 defences and infiltrate the general’s personal quarters – a feat that cannot be attributed to mere luck or lax security but rather to the refinement of stealth and penetration techniques. Furthermore, Hua Yuan 華元 was no common man; he was a distinguished military general whose exploits were later referenced by Sunzi 孫子 (Sun Tzu) himself.

From the historical account of Hua Yuan’s 華元 mission, we witness the use of stealth and penetration for immense psychological impact. Consider the terror that Zi Fan 子反 must have felt – waking in the dead of night to find a stealth operative beside him, deep within a well-guarded camp of thousands of soldiers. In that era, such operatives were often seen as both thieves and assassins, instilling the fear not only for their own lives but for the safety of their families, who were not beyond the reach of these deadly agents.

Authors Note:

From the perspective of understanding the complexities of the Chinese art of stealth, we can observe that even at this early stage in history, a renowned warrior and strategist possessed stealth techniques in his personal arsenal. By studying Hua Yuan 華元, we discover that he was not just an obscure figure or a mere thief; he was a prominent individual, even mentioned by the great Sunzi 孫子 (Sun Tzu). This adds layers of intrigue to our understanding of stealth in historical contexts.

Reference:

The account of Hua Yuan 華元’s stealth mission during the siege of the Song 宋 capital can be found in various historical texts. Here are some key references:

-

Zuo Zhuan (左傳):

- The Zuo Zhuan, or Commentary of Zuo, is a major historical text that provides accounts of the Spring and Autumn period. Hua Yuan 華元’s mission is referenced in relation to the events during the siege of the Song capital. It is often cited for details about military strategies and notable figures of the time.

-

Shiji (史記):

- The Shiji, or Records of the Grand Historian by Sima Qian, may include references to Hua Yuan 華元 and the events surrounding the siege of Song. While the Shiji primarily covers a broader historical scope, it provides context for the military and political climate of the time.

-

Chronicles of the Three Kingdoms (三國志):

- Although this text focuses primarily on the Three Kingdoms period, it also discusses earlier figures and events, including Hua Yuan 華元’s contributions and relevance in military history.

-

Sunzi Bingfa (孫子兵法):

- References to Hua Yuan 華元 may also be found in discussions of strategy within The Art of War by Sunzi 孫子, as he is known to have mentioned notable military figures and their tactics. Hua Yuan’s 華元 actual mission was not mentioned specifically.

-

Wang Chong’s (王充) Lunheng (論衡):

- This work discusses historical events and figures, including those from the Warring States period, offering insights into Hua Yuan 華元’s role and actions.

-

Secondary Sources:

- Scholarly analyses and historical commentaries often discuss Hua Yuan 華元’s mission within the context of the use of stealth in warfare. These works can provide additional interpretations and insights into the significance of his actions. One excellent example is The Tao of Spycraft: Intelligence Theory and Practice in Traditional China by Ralph D. Sawyer.

For the most accurate and comprehensive understanding, it’s advisable to consult direct translations and commentaries of these texts. The historical context surrounding Hua Yuan 華元’s mission serves to illustrate the development of stealth tactics in Chinese warfare.