Yinshen Shu 隱身術, an ancient Chinese art of invisibility, has its roots firmly embedded in the military and martial traditions of China’s Spring and Autumn period 春秋時代 (771–476 BCE) and the Warring States period 戰國時代 (475–221 BCE). During these tumultuous times, stealth, concealment, and deception were not merely tactics but essential skills for survival. Long before Japan had fully developed its own culture, Yinshen Shu 隱身術 was already being refined and practised in China. At this time, Japan was still largely in a ‘stone age’ phase of development, lacking the complex socio-political structures of early Chinese civilisation.

Through our research, we have discovered evidence that Yinshen Shu 隱身術 began its journey across the seas to the Japanese islands around 200 BCE, carried by Chinese settlers and migrating military personal. Despite this, many modern researchers in Japan avoid discussing this topic, or in some cases, outright deny the influence of Yinshen Shu 隱身術 on what would later be called Ninjutsu 忍術. The reluctance to explore this shared history may stem from cultural pride or the desire to preserve Ninjutsu 忍術 as a uniquely Japanese tradition. However, the evidence clearly points to Yinshen Shu 隱身術 as the foundation upon which Ninjutsu 忍術 was built.

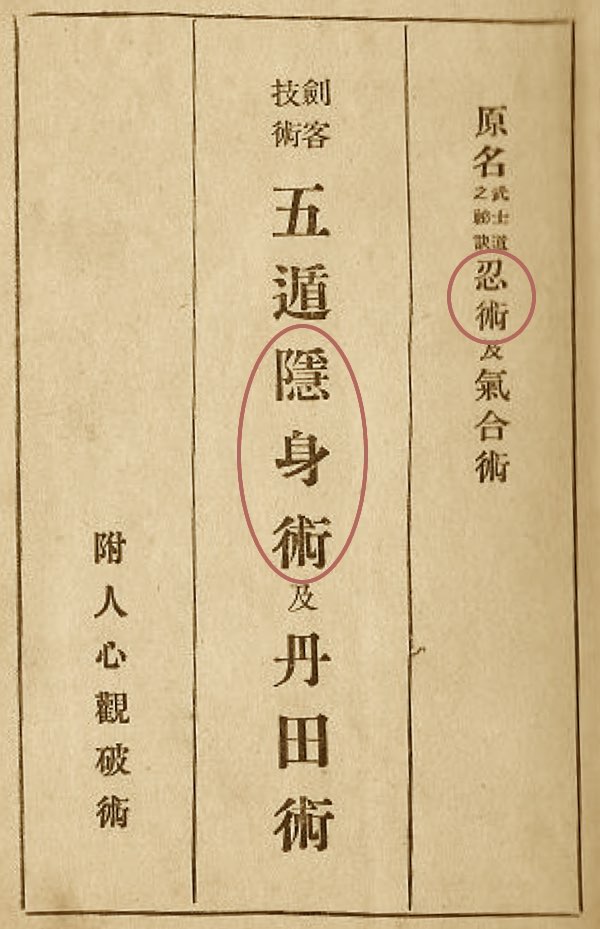

Our research took a fascinating turn when we made an extraordinary discovery—a book authored by the Japanese Ninjutsu Research Society 日本忍術研究會 in Shanghai 上海, China, in 1930. This text, titled The Five Ways of Yinshen Shu and Dantian Techniques 五道隱身術及丹田術, provides irrefutable proof that Yinshen Shu 隱身術 and Ninjutsu 忍術 are not merely similar but, in fact, the same art under different names. The publication from a respected Japanese society directly acknowledges that the Chinese term Yinshen Shu 隱身術 and its Japanese counterpart Ninjutsu 忍術 both reference the same set of techniques and share identical roots. This remarkable finding bridges the historical gap, showing that Ninjutsu 忍術, as practised in Japan, is deeply connected to the original Chinese art of invisibility.

This discovery challenges the long-held belief that Ninjutsu 忍術 developed independently in Japan, revealing instead that it is a continuation of a much older Chinese tradition. The use of both terms side by side in the 1930 publication clearly illustrates that these arts, separated by national borders and centuries of cultural divergence, were understood by the Japanese themselves to be the same. It also highlights the role of early Chinese settlers in shaping the martial traditions of Japan, an influence that is often overlooked or dismissed in contemporary discussions.

In re-examining these links, we are not diminishing the achievements of Ninjutsu 忍術 as it has evolved in Japan; rather, we are enriching our understanding of the shared history between the two nations and the deep roots of stealth and invisibility techniques in East Asia. The existence of this 1930 text opens the door to further exploration, as it is a direct, authoritative source that affirms the origins of Ninjutsu 忍術 within the Chinese tradition of Yinshen Shu 隱身術.

The Japanese-authored book illuminates a crucial aspect often overlooked by contemporary researchers of ninja and ninjutsu 忍術: the interchangeable nature of yinshen shu 隱身術 and ninjutsu 忍術.